From Vox. Click here for the original article.

by German Lopez

It’s a statistic that shows America’s drug addiction crisis is truly an epidemic.

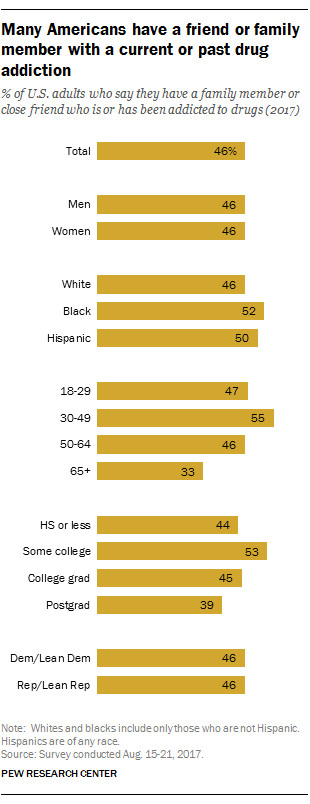

This is America on a drug addiction epidemic: Nearly half of US adults have a close friend or family member who’s been addicted to drugs.

That comes from a Pew survey of US adults conducted in August, which found that 46 percent meet the criteria.

This is what an epidemic looks like: So many people are exposed to drug addiction that nearly half of Americans have a personal experience to speak of. This seems to cut across sex, race, age, education levels, and even partisan lines — no matter how you break it down, a bulk of US adults know someone who has been addicted to drugs.

It’s not just opioids. According to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, in 2016 approximately 20.1 million Americans 12 or older had a substance use disorder. About 2.1 million had an opioid use disorder. The biggest group was for alcohol use disorder, with about 15.1 million reporting an alcohol addiction. (A caveat: Since the survey is based on households’ self-reports, these are very likely underestimates.)

But opioids have been the key driver of the recent US increase in drug overdose deaths, from nearly 17,000 overdose deaths in 1999 to more than 64,000 in 2016. We don’t have reliable drug-by-drug data for 2016 yet, but over the previous few years nearly two-thirds of overdose deaths were linked to opioids.

Last week, President Donald Trump declared the opioid epidemic a public health emergency — activating a very limited set of tools to address the crisis. This week, his opioid commission is expected to release its final recommendations on dealing with opioids.

The opioid epidemic goes back to the 1990s, with the release of OxyContin and mass marketing of prescription painkillers, as well as campaigns like “Pain as the Fifth Vital Sign” that pushed doctors to treat pain as a serious medical problem. This contributed to the spread of opioid painkiller misuse and addiction, which over time also led to greater use of illicitly produced opioids like heroin and fentanyl. Drug overdose deaths have climbed every year since the late ’90s as a result.

The issue has really turned into two simultaneous crises — which Keith Humphreys, a Stanford University drug policy expert, has described as the dual problems of “stock” and “flow.” On one hand, you have the current stock of opioid users who are addicted; the people in this population need treatment or they will simply find other, potentially deadlier opioids to use if they lose access to prescribed painkillers. On the other hand, you have to stop new generations of potential drug users from accessing and misusing opioids.

Addressing two crises at once will, obviously, require a lot of resources. But as I previously explained, we have a pretty good idea of what these resources would go to: They could be used to boost access to treatment, pull back lax access to opioid painkillers while keeping them accessible to patients who truly need them, and adopt harm reduction policies that mitigate the damage caused by opioids and other drugs.

Some states are attempting to confront this issue. Vermont, for example, has built a “hub and spoke” system that treats addiction as a public health issue and integrates treatment into the health care system. Potentially as a result, the state was the only one in New England to have a drug overdose death rate below the national average in 2015. For more, you can read a detailed breakdown of Vermont’s system in Vox’s new explainer.